Chad Aldeman is a freelance writer who served in the U.S. Department of Education during the Obama Administration. He has published reports on school accountability; school finance; and teacher compensation, evaluation, and preparation. His work has been featured in the Washington Post, New York Times, and Wall Street Journal.

As someone who’s had firsthand experience in the ups and downs of the education reform movement, I agree with Matt calling it a “strange death.” Reformers did over-promise, and they did fail at scaling up once-promising ideas.

But we’ve now let the pendulum swing back too far, to a “lol, nothing matters” view on schools, and that’s wrong, too. The left has coalesced around the idea that schools just need more money and support and not much else. The right is using schools as a culture war scapegoat as it wins school choice battles. National media outlets are adding more fuel to those fires, rather than soberly monitoring how students are recovering from the pandemic.

Meanwhile, the essential insights behind the education reform movement have only gotten stronger: Schools matter for kids, schools can get better, and these questions are especially important for the disadvantaged students who rely on public schools the most.

Key insight: Schools matter

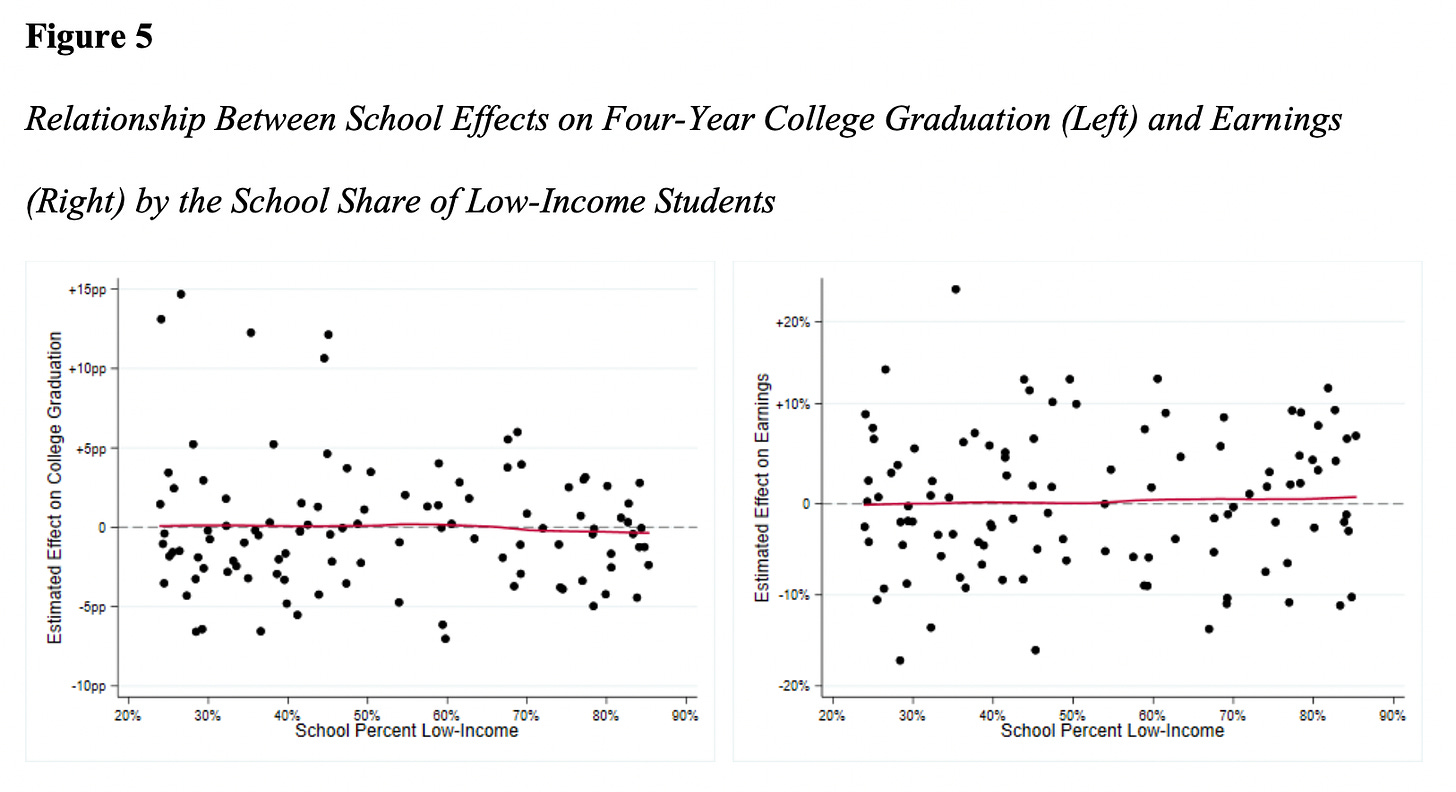

A recent working paper from a team of Brown and Harvard researchers helps illustrate the importance of schools. They studied Massachusetts students who entered ninth grade in 2002 and 2003 and measured college completion rates and labor market earnings at age 30. Because the authors were interested in the effects of the high schools, they controlled for student demographics, incoming test scores, parental levels of education, and the results of a unique survey that the students took as eighth graders asking about their plans for life after high school.

Now, there are a few things worth unpacking here. The first is that, when most people picture a “good school,” they might think of all the inputs the school has, such as the facilities or the teaching staff or the other students attending the school. But this paper was focused on measuring the unique contribution each school made to student outcomes. Did the school improve the trajectories of their students, or not?

It turns out that schools had a big, long-term effect on students. Low-income students who attended a high school at the 80th percentile of quality were 6 percentage points more likely to earn a bachelor’s degree and earned 13% more money (or about $3,600) per year at age 30.

Perhaps more importantly, the authors found that “good schools” could be found across the income distribution. In fact, the authors found basically no relationship between a school's poverty level and its effect on either college graduation or earnings.

These are not particularly novel findings within education. A study out of DC found that high schools with strong “promotion power” for high school graduation also had strong effects on college attendance. Another study out of Massachusetts found that high schools had a bigger effect on college attendance than on test scores.

It’s more equitable—and fair for the school leaders—to evaluate schools based on how much progress their students make, not on point-in-time “status” measures which tend to be more closely aligned with student demographics. Over time, state accountability systems have shifted toward growth measures, rather than merely rewarding (or punishing) a school based on their incoming students’ abilities. But it’s still hard to convince the public that school quality should be defined based on outcomes and not all of the surface-level inputs.

What does a good school do? The Massachusetts paper does a nice job peeling back the short-term indicators that are predictive of long-term success. It turns out that the proxy measures we have for measuring school quality, things like test scores, attendance, and other intermediate outcomes like college-going rates, are pretty good predictors of longer-term outcomes like completing college, finding a job, and earning a decent wage.

These may not be flashy or fashionable, but test scores, attendance, and credit accumulation all had an effect on later-life earnings. While these variables mostly operated independently of each other, the best high schools were ones that were able to both raise academic performance and elevate student aspirations for college.

To be clear, the school quality effects are not large enough to “end poverty in our lifetimes” or any other such bold claims. But that’s setting an impossibly high standard, and we need to be open to a lot of small improvements rather than aiming for one policy to solve all of our problems.

Education Reform Nihilism

The downfall of the education reform movement, such as it was, stems from a lot of causes.

But we’ve now entered into what I think of as education reform nihilism, where nothing that we could possibly do to improve schools would matter all that much. This is best captured by a recent Freddie deBoer piece where he concludes that, “almost nothing moves the needle in academic outcomes. Almost nothing we try works.”

He’s right, up to a point. But he misses the mark on two fronts. One, at the macro level student achievement has improved over time, and gaps are narrowing. DeBoer points to one study suggesting that achievement gaps have remained the same over time, but a more recent, peer-reviewed version of that same paper concludes, “Gaps in math, reading, and science achievement between the top and bottom quartiles of the SES distribution have closed by 0.05 standard deviation per decade.” Other papers come to similarly positive conclusions: Achievement scores are rising, and gaps are closing across income and racial lines.

True, the progress here is painstaking and slow. As one of the papers noted, “At the current pace of closure, the achievement gap would not be eliminated until the second half of the 22nd Century.”

And this is where DeBoer, federal policymakers, and wealthy philanthropists have learned the wrong lessons. It’s not that reforms don’t “work” or that schools cannot improve. It’s more complicated than that. Lots of things can work—there’s a whole federal website called the What Works Clearinghouse documenting thousands of successful reform efforts—but they may not work the same way everywhere.

This is an important distinction, because it means policymakers need to keep their eyes focused on marginal improvements rather than trying to find one big fix. This is the exact opposite of what education policy has looked like over the last 20 years. Notable fads include:

A big national push on phonics-based reading instruction. Congress killed that program, but the evidence around the “science of reading” only got stronger, and there’s now a renewed policy push.

A philanthropy-driven effort helped districts break up large, low-performing high schools into smaller academies. That effort died before the positive results came in, but the idea for small schools is now rising again in a new form.

A publicly funded tutoring program for students in need of additional support. At its peak, the NCLB-funded tutoring program served nearly 1 million students at a cost of $2.3 billion a year. That version of tutoring did not deliver results at scale and was killed off by the Obama Administration, but the evidence on high-quality tutoring has only gotten stronger.

The Obama-era effort to improve teacher evaluation systems. The national effort has famously failed to improve student test scores, but teacher evaluation reforms have been effective in places—like Washington, DC—that tied the results to personnel decisions like compensation.

Alternative teacher preparation pathways. They were once seen as good ways to motivate young people to join the teaching profession, and the highest-profile program, Teach for America, produced strong results. It has been shrinking recently in part thanks to political pushback; meanwhile, new teacher residency models are growing rapidly.

The overarching lesson from these examples is that a whole lot of things can work, but they may not work the same everywhere. That’s ok! Matt also noted some concrete things we could do around air quality and school lunches. These might sound like small beer, but that’s exactly the point: We might have more success with a lot of small things—and tinkering over time—rather than searching for one magic thing.

We’ve lost the thread on school quality

So, schools matter. And we have a pretty good idea about what aspects of schooling matter and how to measure them. This isn’t new or revolutionary stuff. Robert Balfanz, an education researcher at Johns Hopkins University, has long urged schools to focus on the ABCs—A for Attendance, B for Behavior, and C for Course performance and credits—to identify kids who are at risk of dropping out.

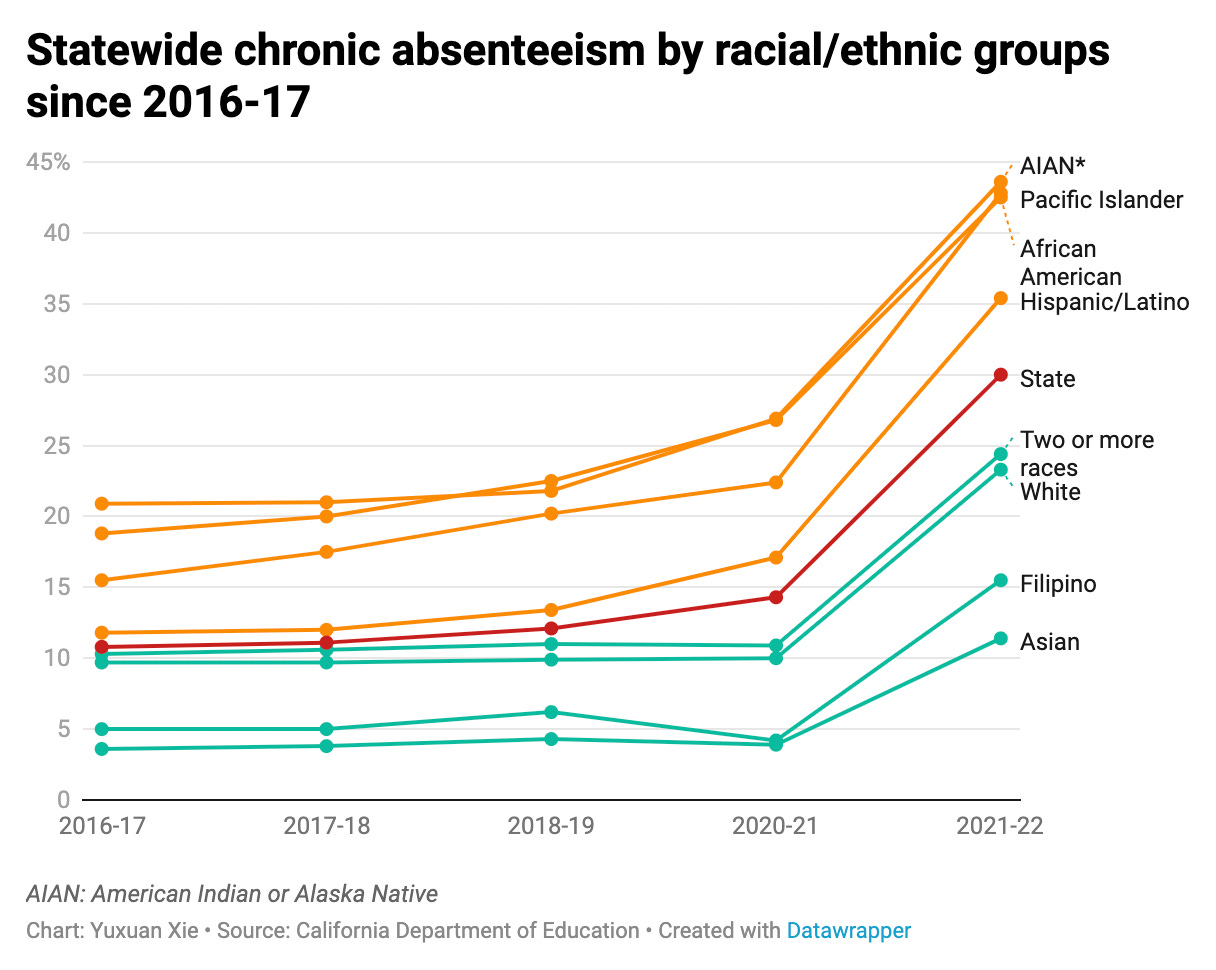

Unfortunately, all of the key student indicators are currently pointing downward. Student achievement fell sharply in the wake of COVID-19 and students are still far below where they otherwise might be. About twice as many students were chronically absent last year than the year before the pandemic, and those rates are especially bad in large urban districts and among historically disadvantaged and low-income students.

Behavioral problems are also rampant. School staff report a surge in disruptive behavior, and 84% of school leaders reported that the pandemic negatively affected behavioral development of students at their school.

We’re already starting to see some intermediate consequences for all this. College enrollment rates are still trending downwards, especially for recent high school graduates from low-income schools.

Of course it’s easier to identify these problems than it is to fix them, but the first step is acknowledging that these issues matter, and something can be done. We’re in a moment right now where policymakers need to re-focus on the importance of getting kids back on track.

It's probably not surprising that young people are far more positive about social media than older people. But I am a little surprised about the big education gap. Is this because of education itself? Or because the kids of high school grads have more problems with social media than the kids of college grads?

It's probably not surprising that young people are far more positive about social media than older people. But I am a little surprised about the big education gap. Is this because of education itself? Or because the kids of high school grads have more problems with social media than the kids of college grads?